INTRO

During the reign of the Soviet Union, the Russians produced several important, and memorable designs, in the field of military aviation. The Flanker and Fulcrum have become the Russian equivalents of the F-15 and F-16, recognisable at a glance, while the Mi-8 and Hind have become two very well-known military helicopter designs.

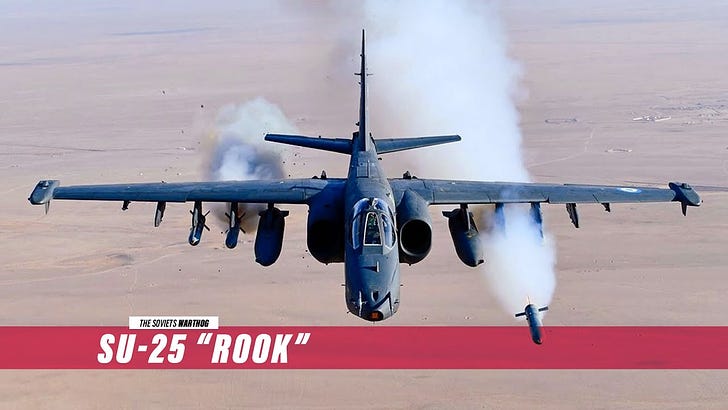

Another of these recognisable designs - seen in movies, video games, and other popular media - is the SU-25 Frogfoot. Designed in the mid 1970s and arriving in the 1980s, it came at a time when the demand for modernised close air support systems was high. It originated during the same period as the American A-10 Warthog - perhaps the most iconic close air support aircraft ever - and while it may not possess the same reputation, it is well known, nevertheless.

Today we will take a look at Frogfoot, Russia’s Warthog, if you like; a battle tested aircraft with a reputation for longevity and strength, it has found favour everywhere from Russia and Ukraine to Africa and the Middle East.

HISTORY

The story of the Frogfoot dates back to the 1960s. During the Vietnam War, the US had relied primarily on conventional bombers and multirole aircraft to deter ground threats. This worked for most tasking, but when it came to troop support it was a different story. Conventional bombers lacked the accuracy to safely support troops, and multirole jets like the Phantom were too fast to act beyond the role of strike aircraft when supporting troops, they had trouble keeping visuals on small targets given their speed, and most aircraft lacked strong armour to protect from ground fire. As such, troop support was most effectively done by helicopters - Huey gunships and Cobras. The only fixed wing aircraft that could really act in a true troop support role was an old design - the A-1 Skyraider.

By the late 1960s, both the US and the Soviets were interested in developing a fixed wing aircraft dedicated to close air support, which would address all the issues encountered when using bombers and multirole aircraft for troop support. For the US, this would be the A-10. In the Soviet Union, it would be Pavel Sukhoi’s design, known as the T-8. The T-8 concept was approved after it won a government design competition against the Ilyushin IL-102.

The Frogfoot would be comparable to the Warthog in the US. The Warthog was designed to be a robust aircraft. Its engines were designed to ingest shrapnel and restart. It had three levels of redundancy thanks to three flight systems, the other two which could keep the aircraft airborne in the event of catastrophic failure to the primary system. It had redundant hydraulic systems for the same reason. It was built in modules to increase safety; the engines were mounted on pylons to prevent fires from spreading to the control surfaces and to limit smoke ingestion from the cannon, whilst at base the entire aircraft could be disassembled into modules for repair or rebuild after heavy damage.

The Warthog had set a new standard for modern aircraft strength, and this would become apparent in later conflicts, when these aircraft would receive heavy damage and return home. The Russians wanted the same to be true of their new design.

Many aspects of the new Russian aircraft were similar, though it was difficult to tell from the outside. Both had a high load rating and could carry enormous quantities of munitions. The emphasis was on close air support and ground attack, and both would retain a limited ability to engage in air-to-air scenarios, albeit only in self-defence.

One major difference between the US and Soviet designs was speed. The Su-25 was considerably faster than its rival; while the Warthog had a top safe speed of around 380 knots, the Frogfoot could be pushed beyond 500. This gave the Frogfoot an edge in some situations, but hindered it in others, depending on the task at hand.

One of the biggest advantages the Warthog possesses over other aircraft is its slow speed. F-16s for example - tasked with close air support - spend considerable amounts of time recommitting to targets, with wide turn circles as the pilot keeps the aircraft above 300 knots. In contrast, the Warthog could cruise around at less than 200 knots, carry more weaponry, and loiter on station for far longer than conventional multirole aircraft.

The Frogfoot on the other hand was faster, limiting its slow loitering capability for drawn out troop support missions, but perhaps giving it the edge when it came to strike missions and other ground attack tasking in contested airspace. In other words, the A-10 is the superior close air support design for loitering missions, while the Frogfoot is likely better suited to operating in an unsecured environment. In any case, both the Warthog and Frogfoot retain good low speed handling, and if enemy aircraft are somehow close enough to merge into a dogfight, these slow aircraft can still demonstrate skilful self-defence moves, especially in a close turning fight.

Regardless, both designs are similar in many ways, both providing far superior close air support capability than the former assortment of bombers and multirole fighters.

After several years of development, the Su-25 would take its maiden flight in 1975, three years after the Warthog first took to the skies. In 1978, the Soviet government gave the go ahead for production of the aircraft, with primary assembly being done in Tbilisi Georgia.

COMBAT RECORD

Following the introduction of the Frogfoot, it would quickly gain international attention. Many Soviet allies at the time wanted such an aircraft since many of these nations - in Africa and the middle east - were regularly engaged in insurgency wars. Before long, nations like Angola, Sudan, Iraq, Ethiopia, Iran and Turkmenistan were operating the aircraft. Likewise in the Eastern Bloc, the aircraft would operate in places like Georgia, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Armenia, Bulgaria, and so on. The aircraft quickly became nearly as recognisable as the Flanker, operating over a good portion of the world.

In 1980, the first Russian Frogfoots were sent to Soviet Azerbaijan, where they would operate in the emerging Soviet/Afghan war. Within months of its introduction, the Frogfoot was proving itself to be a robust aircraft, with zero losses after the first two years, despite many instances of ground fire damage.

The rollout of the aircraft proved so successful that doctrine was changed to accommodate for its use. Soviet commanders were now more comfortable sending troops further into enemy territory. Similarly, the Mujahideen began changing tactics, based on the assumption that Frogfoots will likely be deployed. Later in the conflict, the aircraft would begin operating with precision munitions, like the KH-29 air-to-ground missile, which would be used at altitude to avoid the risk of ground fire.

By 1985, the first Frogfoot had been lost to ground fire, shot down by a Strela-2 missile, and by the end of the conflict 23 aircraft would be shot down while several dozen were lost to other issues, write offs, or damage received on the ground, accounting for a third of all Soviet fixed wing losses during the war.

The Frogfoot would go on to fight in the Iran-Iraq war later in the 1980s, in service with the Iraqi Air Force. Supposedly, in one instance a Frogfoot received a direct hit from a Hawk surface-to-air missile and survived to return to base.

Several of these Iraqi jets would later be destroyed during Operation Desert Storm.

Over the decades, other air forces began to use the aircraft in combat scenarios. In Africa, Ethiopia used the aircraft against Eritrean forces during the Ethiopia-Eritrea war in 1998, while Angola had also used the aircraft during its civil war.

At home, the Russians would task the aircraft in all its regional conflicts. In 1992, the Frogfoot would be flown by three competing air forces: the Georgians, the Russians, and the Abkhazians during the War in Abkhazia. At the same time, further south, the aircraft were also being used by both Armenia and Azeri forces during the First Nagorno-Karabak War.

The most defining conflict from this era was the Chechen Wars, where it would operate closely with the Su-24. During the first conflict in 1994, the Frogfoot primarily operated as a strike aircraft, hitting pinpointed ground targets, but also provided troop support. This culminated in the assassination of Chechen separatist commander Dzhokhar Dudayev, who’s satellite phone signal was pinpointed by an A-50 and relayed to a Frogfoot, which then used two air-to-ground missiles on the position.

By the second conflict in 1999, tactics changed, and close air support and troop support missions would take more priority than they did in the previous conflicts. Frogfoots and Su-24s were also given the task of hunting for targets of opportunity ahead of friendly formations, flying low and using visual identification to spot and strike targets. This tactic became popular at this time. The arrival of the Su-25T also opened up new avenues for night operations and all-weather strikes, which were previously avoided due to the risk of faults with navigational equipment.

In the modern era, we still see this aircraft regularly in conflict. During the 2008 Georgian War, both Russian and Georgian forces employed the Frogfoot against each other’s forces, while in the Syrian Civil War and the war against ISIS, the aircraft has routinely appeared, being operated by a variety of air forces in the Middle East region, as a robust and simple aircraft against insurgents.

But the most pressing conflict, and the greatest test of the aircrafts abilities thus far has been the Russo-Ukrainian War. The cornerstone of air-to-ground capabilities in both the Ukrainian and Russian inventory, the Frogfoot has seen extensive use during the conflict by both sides.

One image, circulating online, showed a Frogfoot returning to base after receiving a direct hit from a Stinger missile, a testament to the strength of the design. During the Kursk offensive, Su-25s provided close air support as Ukrainian troops pushed into Russian territory, while in the southeast, both sides sent their Frogfoots over front lines. This is sometimes done by other aircraft, but the Frogfoot’s strong armour makes it a safer choice for flying below the dense radar coverage of both sides.

STATS

In terms of performance, the aircraft has a maximum speed of 530 knots. Designed principally for low altitude operations, the service ceiling for the aircraft is relatively low, at only 23,000 feet, significantly lower than the Warthogs ceiling of 45,000 feet. Likewise, the range of the aircraft is relatively short. Its maximum range, without tanks, is around 1000km, while its combat range, with 10,000 lbs of weapons and drop tanks is around 750km.

FUTURE

The future of the Su-25 remains unclear. Russia has said that it seeks to upgrade its fleet to a new standard sometime soon, although this doesn’t appear to have begun. Other reports circulate, indicating that the Russian Air Force seeks to slowly phase out the design over the next few decades.

In many ways then, the Frogfoot faces the same uncertainty as the Warthog, who’s future is also up in the air as decision makers grapple with the notion of replacing it with more modern, faster moving strike aircraft. The reality is that both the Warthog and Frogfoot have no ideal replacement; An interesting predicament for both east and west, since no attempt has been made by either side to successfully fill this very niche yet important role; slow, lingering air support for ground troops, able to remain on station for prolonged periods of time, while carrying large amounts of weapons. Only the future will tell whether both sides can risk moving away from these tried and tested designs, or whether they will be kept in service.

But for now, the Su-25 remains one of the most necessary air assets in the Ukraine War, used by both sides for troop support, precision strikes, and neutralisation of mechanised infantry. Its robust design makes it ideal for low level fighting, one of the only aircraft which both sides regularly use beyond each other’s front lines. While proposals exist for the future of the aircraft, what is certain is that while they are still flying in this conflict, it remains an indispensable piece of equipment.